8.2

Indian Censuses and lineage of Bhumihars and Malla-Sainthwars

Contrary to the Maurya

community, the Babhan and Sainthwar communities drew attention of the

historians due to their dominance coupled with ambiguous position in the caste

hierarchy. Out of the two, tracing the lineage of the Mall-Sainthwars is simple

because the community has a low population and thickly settled in Gorakhpur,

Maharajganj, Deoria and Kushinagar districts of Uttar Pradesh. As these

districts are adjacent to each other, the trend in population growth will be

very similar to each other. As Sainthwars are an integral part of these

regions, they must have shown similar trends in population growth as that

witnessed by the regions. To understand whether there is any such correlation,

the population growth of Gorakhpur region is compared with the population

growth of community in the coming section.

8.2.1

Population growth of Gorakhpur region [1]

The first effort in

estimating the population of Gorakhpur was made by Buchanan in 1813. He

considered the number of families and ploughs in each police circle to arrive

on the population number. On this rough and untrustworthy basis, he obtained an

aggregate of some 1,226,110 people, giving an average density of 271 persons

per sq. mile. After some part of Gorakhpur was carved out as separate district

Basti, the population of remaining Gorakhpur Province was recorded by the

censuses of 1872, 1881 and 1891, refer Table 8.2.1a. The number shows very high

growth rate in the period of 1872-1881, but later moderating in the period of

1881-1891.

Table 8.2.1a

Population figure of Gorakhpur Province from 1872 till 1891

|

Year |

Population |

Change in population |

% change in 10 years |

|

1872 |

20,19,361 |

----- |

----- |

|

1881 |

26,17,120 |

5,97,759 |

29.60 |

|

1891 |

29,94,057 |

3,76,937 |

14.40 |

In the year 1946, the Gorakhpur province was

split into the districts of Deoria and Gorakhpur. In 1989, a section of it was

carved out as separate district Maharajganj. The combined population of

Gorakhpur and Maharajganj districts has been given in Table 8.2.1b.

Table 8.2.1b The

combined population of Gorakhpur and Maharajganj districts as per the census

records

|

Year |

Population |

Change in population |

% change in 10 years |

|

1901 |

14,50,884 |

----- |

----- |

|

1911 |

15,80,966 |

1,30,082 |

8.97 |

|

1921 |

16,12,851 |

31,885 |

2.02 |

|

1931 |

18,01,373 |

1,88,522 |

11.69 |

|

1941 |

19,93,661 |

1,92,288 |

10.67 |

|

1951 |

22,38,588 |

2,44,927 |

12.29 |

|

1961 |

25,65,182 |

3,26,594 |

14.59 |

|

1971 |

30,38,177 |

4,72,995 |

18.44 |

|

1981 |

37,95,735 |

7,57,558 |

24.93 |

|

1991 |

47,30,052 |

9,34,317 |

24.61 |

|

2001 |

59,36,497 |

12,06,445 |

25.50 |

|

2011 |

71,01,567 |

11,65,070 |

19.62 |

The analysis of population

numbers reveals that the growth rate in Gorakhpur and Maharajganj districts

followed the same trend that was witnessed by the undivided Bihar than the

undivided Uttar Pradesh, refer Table 7.4.2c and 8.2.1b. The reason may be the

location of these two districts in the eastern part of Uttar Pradesh and adjacent

to Bihar. From both tables, it can be seen that the population of India, Uttar

Pradesh, Bihar and the combined districts of Gorakhpur and Maharajganj

increased by 5.07, 4.31, 5.01 and 4.89 times respectively in the period from

1901 to 2011.

8.2.2

Population of Mall-Sainthwar community

The population of community

from 1865 to 1931 has been given in Table 8.2.2a. The census of 1865 records

the total population at 59,823 in Gorakhpur Province while 2,573 in Azamgarh

Province (now Mau district). The total population of the community was slightly

higher than the above numbers due to non addition of its minority populations

settled in the western part of Bihar and Nepal. Comparing the growth rates in

the period of 1865 to 1891, it can be seen that the community as well as the

province witnessed their population increasing by 1.5 times, refer Table 8.2.1a

and 8.2.2a. In the later years, the community showed 30% growth in the period

of 1891–1931 while the combined districts of Gorakhpur and Maharajganj witnessed

25% growth in the period of 1901-1931. Therefore from 1865 till 1931, the

community showed similar growth in its population as that witnessed by the

Gorakhpur province.

Table 8.2.2a Population of Mall - Sainthwar community

|

Year |

Total Sainthwar population |

Mall in Mau district |

Indian Census |

|

1865 |

59823 |

2573 |

Census of the North-West Provinces 1865. |

|

1881 |

|

3218 |

Northwest Provinces of Agara and Oudh Native State Rampur and Gadhwal , as Kurmi caste |

|

1891 |

98660 |

|

As Kurmi caste |

|

1911 |

118982 |

|

As Sainthwar caste, United Province of Agara and Oudh |

|

1921 |

123424 |

|

As Sainthwar caste, United Province of Agara and Oudh |

|

1931 |

133254 |

|

As Sainthwar caste, United Province of Agara and Oudh |

The census of 1931 was the

last caste based census of India. As the population numbers of the country,

states and districts under consideration showed an almost similar growth rate

till 2011, there is no reason to believe that the community (or the

communities) population will show large deviation from its surrounding

environment when projected for long periods. Therefore, applying the

approximation of 440% growth in the period of 1921-2011, as witnessed by the

Gorakhpur and Maharajganj districts, the population of Malla-Sainthwar

community in the year 2011 will be around 543,000, refer Table 8.2.2b. The

approximate population number for the ancestors of the community in the year

1600 AD and 300 BC have been arrived on the basis of population estimates put

forward by various scholars who show that the population of India in those

periods was approximately half of the numbers recorded for the years 1872 and

1921.

Table 8.2.2b: Approximate population of Malla - Sainthwar community on time scale

|

Year |

Sainthwar |

Mall in Mau district |

Notes |

|

300 – 600 BC. |

30,000-60,000

|

1,250-2,500

|

Back calculated as per population growth of the Indian subcontinent |

|

1600

|

30,000-60,000

|

1,250-2,500

|

Back calculated as per population growth of the Indian subcontinent. |

|

1865 |

59,823 |

2,573 |

Census of the North-West Provinces 1865 |

|

1921 |

123,424 |

|

Census of United Province of Agara and Oudh |

|

2001 |

440,000 |

12,500 |

Projected as per population growth of combined districts of Gorakhpur and Maharajganj for 1901-2001. |

|

2011 |

528,000 |

15,000 |

Projected assuming same growth rate of Gorakhpur and adjoining district population |

Since the combined

population of Gorakhpur, Maharajganj, Deoria and Kushinagar districts of Uttar

Pradesh was 13,760,034 in year 2011 and the projected population of the

Mall-Sainthwar community was around 543,000, the community has population

strength of nearly 3.5 - 4% in the society of these regions.

8.2.3

Population of Babhan or Bhumihar community

For Bhumihars, a similar projection for their population has been already made in Table 7.4.3 and it can be fairly considered as accurate for the year 2011. The majority population of the community is settled in the states of Bihar and Jharkhand. The combined population of both states was around 28.1 million (2.81 crore) in the year 1921. The total population of Bhumihars is recorded at 1,167,373 in the census of 1921. Therefore, if undivided Bihar is considered as their ancient origin, the population strength will come around 4%. However, they are scattered across many other states and therefore the effective percentage population in Bihar is only 2.9%. [2]The estimated population numbers of both communities over a large time scale confront the various origin theories given by historians. However, before going into detail in this, it is necessary to understand the early census process which records the population of both communities under different caste or Varna. The understanding is also important as the census data is used to prepare reports on various social issues haunting the Indian republic.

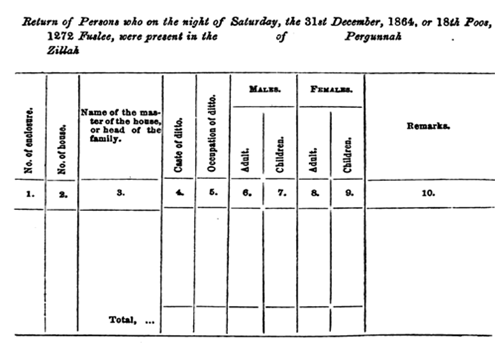

8.3 The

Indian Census of 1865

The early Indian censuses

and their procedures, if scrutinized properly, had some loopholes in it. The

early census carried in 1852, was a regular house to house numbering of all the

people in the Provinces at one fixed time i.e. the night of December 31, 1852.

In 1853, the first attempt to take an accurate census of the north-west

provinces was made under the orders of Lieutenant Governor, the Honorable J.

Thomson. However due to the mutiny of 1857, the next census was ordered on 24th

October 1863 and the same was completed in 1866. In the census, the details of

a family were recorded on a sheet as per Fig. 8.3. The ‘Circular Order No J of

1864 from Secretary, Board of Revenue, N.W Provinces, to all District Officers,

N.W Provinces including Ajmere – Dated Allahabad, the 7th June 1864’ states

that -

1. The mouzahwar returns will be prepared for every separate abadee, whether

principal village or subordinate hamlet (nuglah, poorwah, muzrah, astul etc…).

The same form will be used in cities and towns for each mohullah or other

convenient sub-division. In column 1, each enclosure (ihatah) will be entered

by serial numbers.

2. In column 2, by the term ‘house’

or ‘family’ is meant those who live together, and ordinarily cook their food at

the same hearth (choolah).

3. In column 3, the name of the head of the family will be entered.

4. In column 4, the caste of

the person entered in column 3 will be noted. It will not be necessary to

record minute sub-divisions of the castes; it will be sufficient to enter the

more general and well known denominations as Tewaree, Pandey, Doobey, Misr,

Bughel, Bais, Kuchwar, Ugurwala, Ugruhree, Kusurwanee, Kayuth and Synd, Sheikh,

Puthan, Mogul, Jolha,…..

5. In column 5,

the occupation of the person whose name is entered in column 3 will be entered.

When the person derives the whole or any part of his subsistence from land, the

word ‘agriculturist’ will be entered; otherwise the particular occupation will

be entered.

Fig

8.3- Census return form used in 1865

In the census process, the

enumerators were generally Putwarees and their relations. The superintendents

were generally pound mohurrirs, superior zamindars, putwarees, schoolmasters

and omlah. The work of testing was done by tehseeldars and canoongoes and in

some cases Peshkars and other tehseeldar officers.

8.3.1

Loopholes in the census of 1865

There can be many errors in

the census of 1865 as it is the first caste based census of India and the

Britishers were having little knowledge about the complexity of caste system.

In the entire process, the Britishers were fully dependent on the orthodox

Brahmins for deciding the caste of a community and their classification on the

Varna ladder. We must not forget that by this time translations of the Pali

texts in English or Hindi were not available and thus histories of many

communities were still buried. While submitting the final census to the British

government, W. Chichele Plowden (Secretary, Board of Revenue, North Western

Provinces) on 13th April 1867 pointed towards some of the errors. The summary has

total 324 points out of which few are mentioned below.

Point No. 278 states that

‘The statement of the castes may be accepted as correct in so far as it

classifies the primary castes; but the details of the sub-castes are only

approximately correct, as it is evident from the tables that in some cases no

distinction of sub-ordinate castes has been observed’.

Point no. 290 states that

‘It will be observed from the statement already given of the numbers in the

different classes that the Agricultural comprises more than half of the total

population. In reality it comprises far more, for to this class should be added

those entered under order XVI; who are as much agricultural as anything else.

Adding these, the agricultural class will be 21,342,403, or two third of the

population. (17,517,447 agriculturist + 3,824,956 laborers).

Point No. 293 states that

‘The bulk of the agriculture class is formed of agriculturist, proprietors of

land, cultivators and laborers. The distinction between proprietors and

cultivators has not, however, been carefully observed, and it would appear from

the statement that the middle term agriculturist has been indiscriminately

adopted, so as to embrace both proprietors and cultivators’.

Point no. 22 (No. 181, paras

2 to end) of the letter, dated 20th April, 1865 from R.M. Edward (ESQ,

Collector of Bareilly) to J. Inglis (ESQ, Commissioner of Rohilkhand) states

that ‘The statement of Castes I regard as simply impossible to work out with

accuracy. It is not improbable that every district officer in these Provinces

has recorded the results in a different way. Castes are now so mixed up that

the name of the occupation or trade has come to be frequently styled the name

of the caste, as for instance, ‘Zurghur’ though no such castes exists.

The report, dated 6th March

1867, from G. Ricketts (Collector of Allahabad) states that – ‘The source of

the limited information I have been able to collect regarding Hindoo castes are

for the most part the vaguest family traditions, such a thing as a record of

any castes, or any family history, nowhere exists. The traditions, as might be

expected, are strange combination of bad history, impossibilities and fanciful

stories – all firmly believed, and all tending to exaggerate the importance of

tribes and families to which they relate.’

8.3.2

Sainthwar, Bhumihar communities and the Census of 1865

In the census of 1865, the

Britishers classified all communities in four Varna. They placed most

communities, not having any social ties with Brahmin, Rajputs and Vaishyas, in

the Shudra category. The populations of the Mall-Sainthwar community are placed

in the Shudra category in the Gorakhpur and Azamgarh provinces. In Gorakhpur,

the community is recorded as Kurmi Sainthwar and in Azamgarh it is recorded as

‘Mull’ caste distinct than Kurmis. As evident from the summary (point no. 293

and 290) of W. Chichele Plowden, it seems that the census officers were not

able to correlate two things or they were manipulated about the Sainthwars -

1. The difference between

Sainthwars (the proprietors of land) and Kurmis (the cultivators) within the

agricultural class.

2. Malls of Gorakhpur and Malls of Azamgarh provinces – both recorded as

different castes.

Point no. 2 is interesting

as the Malls of Gorakhpur and Azamgarh belong to one and the same clan

(exception BisenMall). It is a major drawback of the census which considered

the Malls of Azamgarh as distinct caste, but ‘Malls’ and their social relatives

‘Sainthwar’ of Gorakhpur as ‘Kurmi Sainthwar’ caste. As the caste system of

India was very rigid in nature and clearly demarcated two communities, the Mall

and their relative Sainthwars of both provinces can be either ‘Kurmi’ or a

‘distinct caste’ but cannot be both.

For Bhumihar community too,

the populations in Gorakhpur and Banaras provinces are placed in Brahmin Varna

while those in Azamgarh and Mirzapur provinces are placed in Kshatriya Varna,

refer Table 8.3.2a. The classification of the community in different Varna

either resembles the confusion prevalent in the upper caste of society about

their origin or the influencing power of Bhumihars because of the dominant

position coupled with high population across eastern Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and

Jharkhand and therefore possibly acting as census enumerators at many places. Overall,

the classification of the community in different Varna again highlights the

drawback of the entire census process.

Table 8.3.2a - Bhumihar populations under different Varna in different provinces

|

Provinces |

Population |

Category |

|

Goruckpore (Gorakhpur) |

30739 |

Brahmin (Bhooenhar) |

|

Azimgurh (Azamgarh) |

44642 |

Kshatriya (Bhooenhar) |

|

Mirzapore (Mirzapur) |

4241 |

Kshatriya (Bhoonheear) |

|

Benares (Banaras) |

21460 |

Brahmin (Bhooinhar) |

The confusion over

classification of communities on the caste scale was not limited to the

Mauryas, Bhumihars and Malla-Sainthwars only but it happened with many other

communities across India. These confusions are clearly mentioned by R.M. Edward

who indicates mixing of the occupation with caste in the census report. The

confusions must have taken place due to one or the other following reasons -

1.

No difference between the agricultural populations such as – the proprietors of

land, the cultivators, the laborers etc.

2. Taking only occupation as an indicator of the caste and clubbing all

communities following a given occupation under one caste

3. No social relations with other land holding community i.e Rajputs /

Kshatriyas

4. Low population

5. Vested interest of some influential Zamindars who acted as Census

Superintendents.

8.4 The

Census of 1881-1901

W. Chichele Plowden

concluded the census report of 1865 with remarks (point no. 316) that ‘It will

be advisable also to furnish the enumerators with a standard list of castes and

occupations, especially of the latter. This will ensure uniformity in the

classification’. The suggestion advocated the classification of communities on

the caste scale as a function of their occupation and therefore seeding the

possibility of the great errors in the classification of agricultural

communities who formed 2/3rd of the total population. The suggestion was

implemented in the census of 1881. The Sainthwars (including Mall) of Gorakhpur

were clubbed with the other populations known as Kurmi and recorded as ‘Kurmi’

in the census than the earlier classification of ‘Kurmi Sainthwar’. However,

this census too recorded the ‘Malls’ of Azamgarh as a distinct caste with a

population of 3,218.

Soon after the census, the

Census Commissioner of individual provinces was flooded with claims of wrong

classification of the castes. The claims were obvious as there were many

communities, especially agriculturist, whose occupation looked same but caste

was different. As a result in 1901, the Census Commissioner of India directed

the census superintendent of each province to draw up ‘the order of social

precedence of castes recognized by public opinion’. In the new system

‘representative committees’ were formed at the district level. These committees

considered the scheme and discussed which caste should be placed in which group

and what order. After the entire survey was done, serious differences emerged

between the district committees on certain castes. For example, some castes

which were put in high order in one province were put in low order in another

province. There were other mistakes too. One of the biggest mistakes was

clubbing of all communities having different occupations and social ranking under

one caste just because they had a similar social name. The most cited example

for this is Dom community who lives in the hills of Uttar Pradesh. The census

report considered them same as the Dom of the plains. It is well known that the

former is a collection of communities whose traditional occupations (mainly

artisans and touchable) differed from that of the latter (scavengers and

untouchable). The entire process of ordering the communities on the caste scale

left so much acrimonious discussion and ill-feelings that the process was not

taken in the coming census.

8.5

Bhumihar, Sainthwar and the censuses of 1911-1931

After the flood of

requests for rectification of the castes in the census of 1901, the Indian

census report of 1911 defined ‘caste’ as – ‘Endogamous group or

collection of groups bearing a common name and a common traditional

occupational, linked together by these and other ties, such as the tradition of

a common origin and the possession of same tutelary deity, and the same social

status, ceremonial observances and family priests.’ [3]

The new definition

of caste addressed all the earlier loopholes. It also considered the distinct

features of caste like –

1.

Marriage within the section to which a person belonged by birth and outside a

sub-caste was prohibited.

2. Caste imposed restrictions on inter-dining and exchange of foods and drinks.

3. The rules and restrictions observed by a caste reflected and determined its

position in the hierarchy of castes.

4. Traditionally the ‘high caste’ practiced ‘child marriage’ and ‘dowry’ while

the ‘low castes’ paid bride price and allowed widow marriage.

After the new definition of

caste, the Bhumihar and Sainthwar populations were separated from their wrongly

classified Varna or caste. The Bhumihars were officially recognized as

Brahmins. The Sainthwar in Gorakhpur and the Jatav in western Uttar Pradesh

were separated from the Kurmi and Chamar castes respectively. This way the

Sainthwar community was recorded as a distinct caste under the Shudra category

with a total population at 118,982. The settlement of 1919, Gorakhpur shows

that the populations coming under Sainthwar caste were mainly landholders, an

important observation which the earlier censuses discounted by labeling all

communities as ‘agriculturist’ if they derived their whole or even part

subsistence from agriculture (refer paragraph 8.3). A better approach of

recording the caste of a person was taken in the census of 1921 wherein the

enumerators were instructed to enter the caste name by which a family is known

in his neighbors [4]. In this census, the populations known as ‘Babhan or Bhuinhar

Brahmin’ and ‘Malla or Sainthwar’ were recorded with a total population of

1,167,373 and 123,424 respectively. The census of 1931, which was the last

caste based census of India, records the Sainthwars and Bhumihar Brahmins as

landholding castes. The very same period witnessed greater understanding about

some communities whose histories were buried in the Pali texts and

archeological sites. In 1942, the discoveries led to E.D.C. Mass (the District

Magistrate of Gorakhpur) ordering rectification in all government records for

replacement of Sainthwar caste with Kshatriya.

8.6 The reliability of Census data and process [5]

With the help of the census,

the Britishers took the marathon task of classifying the entire human

population living in the subcontinent according to their affiliation to a

religion and group (caste). The entire process was very challenging to them due

to various reasons. First, the Indian society was neither subscribed to a

single faith nor evolved from a single human race. The Indian society of

British era was the combination of Negroid, Australoid, Mongoloid and Aryan

races of humans and their interbred who all had different dialects, rituals,

traditions and religious orientations. Second, the British society was based on

the class system (occupation) and therefore natural biases in the

classification process from the occupation angle. Britishers tried to equate

their class system with the caste system of Indian society. They saw caste as

an indicator of occupation, social standing and intellectual ability. Third,

the Britishers took religious texts of land as a reference for classification

of communities on the caste scale. In most texts other than that of Buddhist

and Jain, the Brahmins (priestly occupation) are shown occupying top position

in society. Although religious texts are helpful in deciding the hierarchy

between Brahmin, Kshatriya and Vaishya populations from the occupational angle,

the same are unable to give detailed guidelines for Shudra populations that

constitute 75-93% of total population depending on the geographical locations.

Fourth, the Britishers relied on the learned Indians for data collection,

classification and giving a hierarchy to all in the caste system. Any Indian

can understand the fact that for learned census takers of late 19th and the

early 20th century, who mostly belonged to the upper three castes of the

society, it could have been very difficult to go at the door of lower caste

people and then discussing with them about their data as it could have given a

feeling of loss in dignity or self-respect. Therefore it is very likely that

the individual census takers filled out most of the data themselves without

consulting each individual in the area. Moreover, those Indians who were used

as advisors certainly had more than ample opportunity to act in a manner that

suited their own or their group's agenda since the precedent was based on

interpretations of the writings of the various Hindu holy texts, which were

again manipulated by the orthodox Brahmin class from ancient times for their

own benefit. To even a marginally cynical mind, this would suggest immense

possibilities for graft and corruption. This in turn suggests wrong feedback to

Britishers through manipulation in census data, at least to some degree by

their mainly Brahmin or influential Zamindar informants.

It is widely believed in

present day India that the caste remained an important social subject for all

populations from the ancient times and therefore in the census too. Contrary to

the belief, it was not so. The caste returns in the census were subjected to

several errors. Ignorance and carelessness led to reporting of gotra,

sub-caste, title or occupation in the place of caste. In some cases, identity

of names of sub-castes and sameness of occupation caused confusion. In fact,

the ignorance about caste by most Indian populations led many socialist to

believe that the caste system got an actual hierarchy and a tag for the masses

only after the census and before that caste as a (hierarchical) concept was

restricted to only Rajputs / Kshatriyas of northern India and the Brahmins,

Vaishyas across India. For the majority, the caste could have meant only the

endogamous group in which they have to make their social relations. In words of

Kevin Hobson ‘It is not difficult to imagine a situation where, Brahmins,

seeing the ascendancy of British power, allied themselves to this perceived new

ruling class and attempted to gain influence through it. By establishing

themselves as authorities on the caste system they could then tell the British

what they believed the British wanted to hear and also what would most enhance

their own position. The British would then take this information, received

through the filter of the Brahmins, and interpret it based on their own

experience and their own cultural concepts. Thus, information was filtered at

least twice before publication. Therefore, it seems certain that the

information that was finally published in the census was filled with

conceptions that would seem absolute fraudulent to those about whom the

information was written. The flood of petitions protesting caste rankings

following the 1901 census would appear to bear witness to this. The British

were confused because when they asked Indians to identify the caste, tribe or

race for census purposes, they received a bewildering variety of responses.

Often the respondent gave the name of a religious sect, a sub-caste, an

exogamous sept or sections a hypergamous group, titular designation, occupation

or the name of the region he came from. Obviously Indian self identifying

concepts were quite different from those concepts that the British expected. In

response to this problem, those in charge of the census data took it upon

themselves to: ‘begin a laborious and most difficult process of sorting,

referencing, cross-referencing and corresponding with local authorities, which

ultimately resulted in the compilation of a table showing the distribution of

the inhabitants of India by caste, tribe, race, or nationality. Certainly this

leaves a great deal of room for error.’

Based on these facts, it can

be said that the early censuses captured the sentiments of orthodox Brahmins

and the allied castes towards other communities. As there was a persistent

effort to minimize confusion, the caste statistics in the censuses of 1911 to

1931 were considered to be reasonably accurate by the census superintendents.

In spite of some flaws, the caste based census had its own importance as it

initiated the mapping of populations with respect to their occupation,

settlement, dominance and other social parameters. The data later helped

historians, academicians in their research work and the Indian government too

for starting various welfare schemes. On the negative side, the caste based census

unknowingly threw the whole Indian society in an officially recognized

hierarchical society and therefore feeling of being superior or inferior to

others which was not the case earlier in true sense for the majority of the

populations as they were least bothered about such things and struggled for

their daily needs.

8.7 Evolution of Bhumihar Brahmin

community - Click here to read

********************************************************************************************************************

********************************************************************************************************************

References:

[1] http://gorakhpur.nic.in/gazeteer/chap3.htm

here

[2] Jaffrelot,

C. (2003). India’s Silent Revolution: The Rise of the Lower Castes in

North-India, p. 72. UK: C. Hurst & Co.

[3] Kanmony,

J. C. (2010). Dalits and Tribes of India, pp. 37-38. New Delhi: Mittal.

[4] Chaudhary,

P. Political Economy of Castes in Northern India, 1901-1931, p. 42. New Delhi:

JNU.

[5] Kevin Hobson – ‘The Indian Caste System and The British: Ethnographic

Mapping and the Construction of the British Census in India’

******************************************************************************************************************************

******************************************************************************************************************************

Index Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Chapter 5 Chapter 6 Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Chapter 9 Chapter 10

Give your feedback at gana.santhagara@gmail.com

If you think, this site has contributed or enriched you in terms of information or knowledge or anything, kindly donate to TATA MEMORIAL HOSPITAL online at https://tmc.gov.in/

and give back to society. This appeal has been made in personal

capacity and TATA MEMORIAL HOSPITAL is not responsible in any way.

********************************************************************************************************************

********************************************************************************************************************